Richard Cross

I started photographing the landscape as a way to engage with the natural environment. Using a drone to shift perspective, these images are part of an ongoing project exploring how we see, use and value the Scottish landscape.

Images, text and website © Richard Cross

-

Introducing What Lies Beneath

A short film (2m14s) introducing What Lies Beneath — and how using a drone has changed both my photography and the way I see the Scottish landscape.

-

The Great Outdoors – Photo Essay

I’m delighted that The Great Outdoors magazine has featured a piece about my project What Lies Beneath in their September 2025 issue.

-

Scottish Landscape Awards 2025

My image Potato Furrows has been awarded a Highly Commended in the Scottish Landscape Awards 2025, organised by the Scottish Arts Trust.

About What Lies Beneath

Using aerial photography to explore the Scottish landscape.

Our understanding of the Scottish landscape is shaped not just by what we notice — but by what we overlook. It’s filtered through layers of history, education, and economics — through what we’ve been taught to value, and what we’ve learned to ignore. The camera, too, can reveal or obscure. For years, my photography followed the conventions of traditional landscapes: wide vistas, dramatic light, shifting weather. These images were real, but selective — aligned with a visual language that celebrates beauty, while excluding human impact.

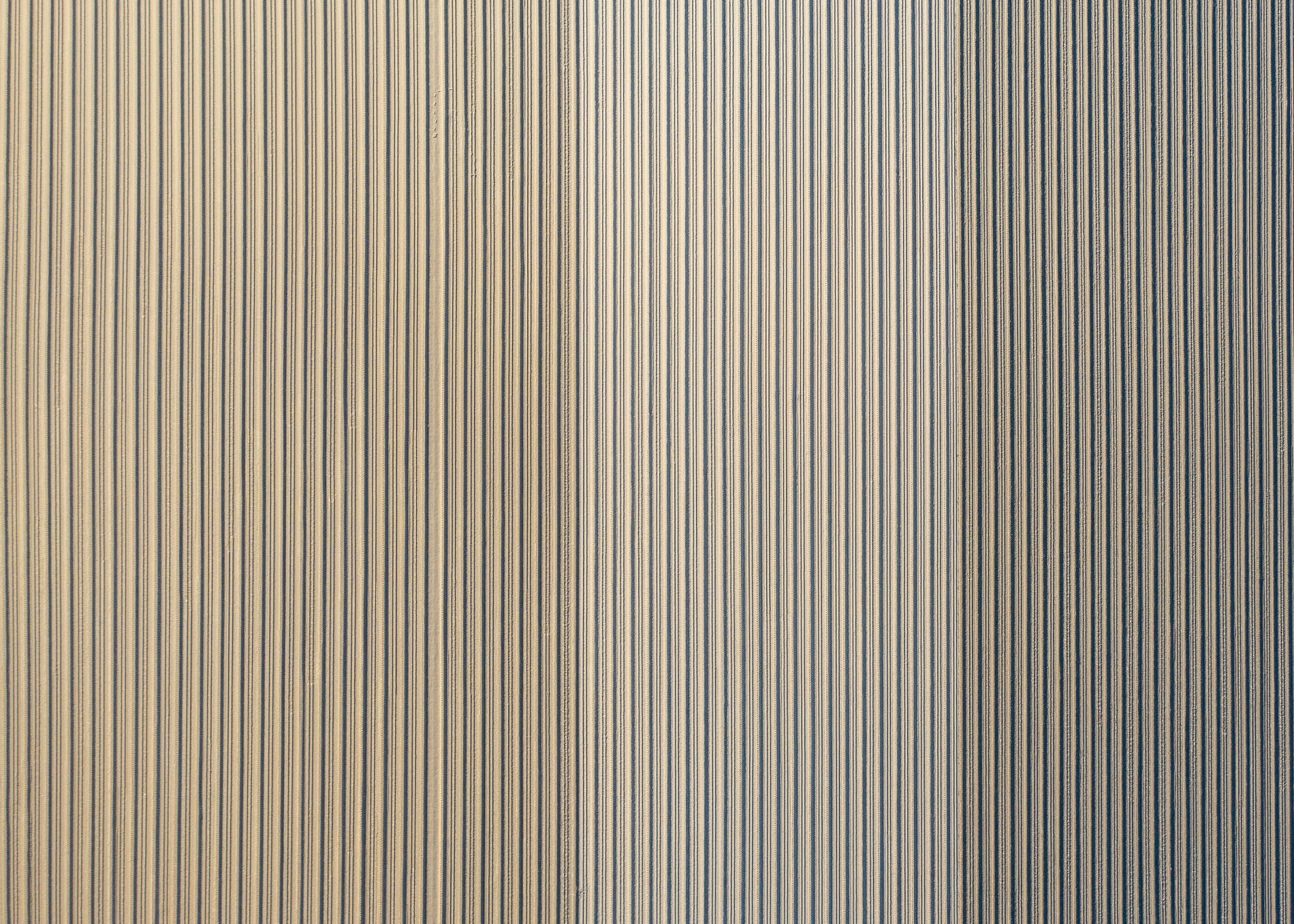

What Lies Beneath began as an attempt to look more closely, and more critically. It pairs images taken at the same location: the familiar landscape view, and a straight-down aerial perspective captured with a drone. These paired photographs expose patterns in the land and traces of human presence — many of which are easily missed from ground level.

The Illusion of the Natural

In Scotland, it’s easy to fall into the myth of wilderness. Much of what appears wild is, in fact, managed. These interventions are so familiar they are invisible, we don’t see them because we are not looking for them. But from above, they become hard to ignore.

Photography encourages us to pay attention. Working with a drone has expanded that practice for me, helping to make visible the layered history and ongoing transformation of the landscape. I began to notice deer paths etched into hillsides, old dwellings, drainage channels and access tracks. These marks tell stories: of control, of use, of change.

A Creative and Ecological Practice

This project sits somewhere between creative exploration and ecological documentation. It comes out of 30 years of photography and walking, shaped by a background in documentary image-making and a growing concern with land use and biodiversity.

I don’t see the drone as distancing me from the land. It’s a tool that deepens my relationship with place. Most of the images I make emerge from time spent walking, returning to familiar spots, seeing them in new conditions. The aerial perspective doesn’t replace that experience — it adds to it. It offers a way to step back, to think more broadly about what I’m seeing.

Shifting Baselines

Some of the landscapes in What Lies Beneath are visibly degraded. Others show tentative signs of renewal. In either case, the paired images offer a way to reflect on our shifting baselines: how each generation comes to accept a more diminished version of nature as normal.

What was once considered barren might now be called pristine. But these terms are slippery. Part of this project is about making those shifts visible. Not to pass judgement, but to pay attention.

In some cases, the images capture tension. Forest plantations versus native woodland. Hydro schemes alongside peatland restoration. Tracks built for sport in areas designated for conservation. But they also reveal where the land is healing: trees reappearing, bogs rewetting, wildlife corridors emerging.

A Personal Evolution

This project marks a change in my own practice. It’s a move beyond traditional landscape photography into something more layered, shaped by reading, walking, listening, and learning from others — ecologists, land managers, historians, and communities.

At its core, What Lies Beneath is about perspective. Both in the literal, photographic sense, and in how we understand and relate to land. It doesn’t offer conclusions. It invites questions.

What does the land remember? What stories do we overlook? And how might seeing differently help us imagine different futures for these places?

Continuing the Work

What Lies Beneath is an ongoing project, not just about documenting change — but about creating space to reflect on what that change means.

Land use in Scotland is once again under scrutiny. Conversations around rewilding, regeneration, access, and land reform are becoming more urgent. Photography won’t resolve these debates, but it can contribute — helping us to notice, to question, and perhaps to see more clearly what’s at stake.

Looking Ahead

Over the coming months and years, I plan to expand the project both geographically and thematically — revisiting existing sites to track seasonal and environmental change, while exploring new locations that reflect the diversity of Scotland’s land use.

I’m actively looking to connect with landscape-scale projects and organisations working in restoration, ecology, or sustainable land use — with a view to building creative partnerships that bring together artistic practice and environmental insight. I’m also exploring the potential for bursaries or residencies that would allow me to spend extended time in particular places, deepening the work and sharing it more widely.

Ideas for presenting the work in physical spaces — exhibitions, installations, and workshops — are in development, as is the longer-term ambition of producing a book. But for now, the work continues: walking, observing, returning, and seeing what lies beneath.

Richard Cross, 2025